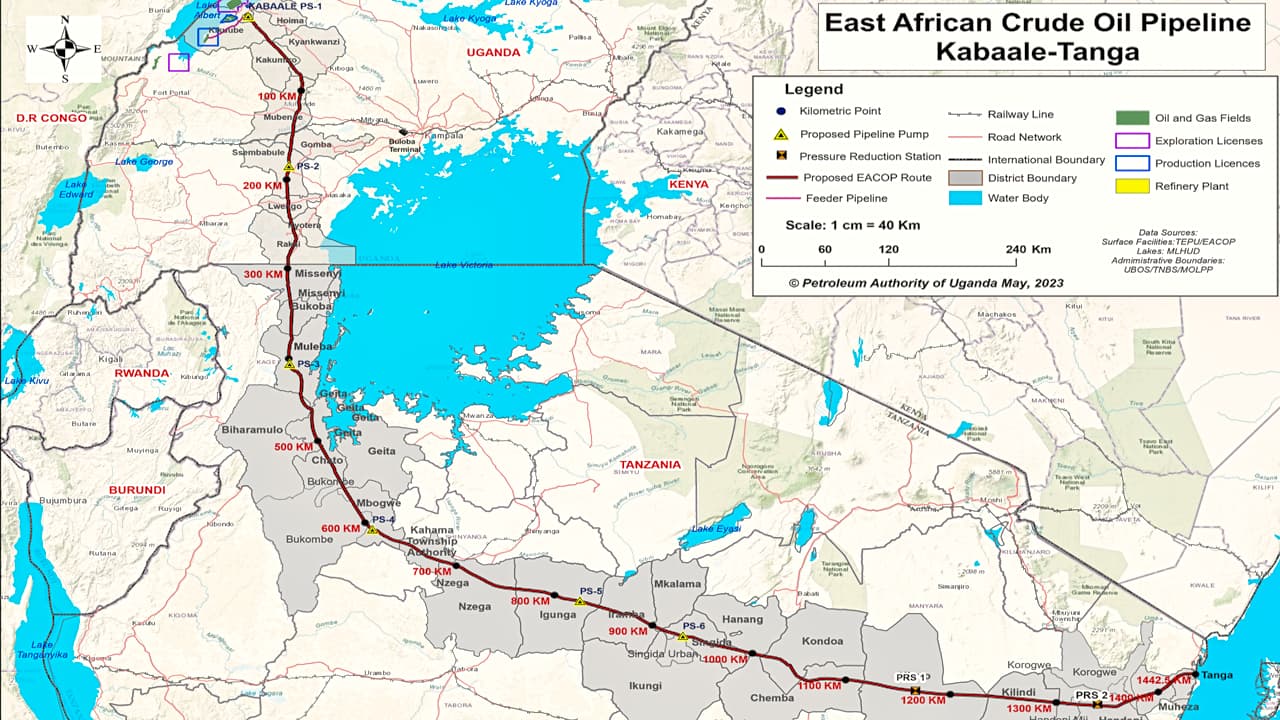

The Petroleum Authority of Uganda has shared fresh details about the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), which will transport oil from Uganda to the Tanzanian coast and, when completed, will be the world’s longest heated crude oil pipeline.

The pipeline, which is expected to cost about Shs4bn, is the centrepiece of Uganda’s oil and gas ambitions; the country expects to start pumping crude in 2025.

“With its extensive fibre-optic network enabling online connectivity, EACOP promises to be one of the smartest and safest bulk pipelines in the world, with real-time satellite monitoring along its entire length,” said Dozith Abeinomugisha, director in charge of midstream development at the Petroleum Authority of Uganda.

Safety personnel will be able to detect pressure changes within seconds that could indicate a leak, sabotage, or theft, and isolate the affected section to minimise environmental damage and commercial loss.

Both PAU and EACOP’s holding company will operate real-time monitoring centres at their offices to receive instant updates via satellite uplink. This approach provides a high degree of dependability as monitoring is independent of local mobile phone or radio networks.

The pipeline will use the SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) system for remote monitoring and data transmission. Despite being buried between one and three metres underground, safety personnel will have access to a complete live picture of the entire installation.

The system will also use renewable energy wherever possible for pumping, heating, monitoring, and storage to help mitigate the effects of climate change. The Ugandan section will be fully carbon-neutral and will be powered by 80MW of solar and hydropower. The development of comparable renewable energy capacity on the Tanzanian side is currently underway.

The design and construction of EACOP, which began in 2018, has been one of the biggest challenges in African infrastructure engineering in recent history.

First, engineers had to figure out how to pump crude oil that is not liquid at surface temperatures — and therefore resistant to flow — but instead has a waxy, shoe polish-like consistency.

The typical solution for such ‘sweet’ crude, which solidifies after being extracted from high-pressure, high-temperature reservoirs deep underground, is to heat the pumping infrastructure to keep it in liquid form.

But the colossal 1,443 kilometre length of the East African pipeline — more than twice the length of the current longest heated crude oil pipeline, the Mangala Development Pipeline, which stretches 670km across the Indian state of Gujarat — was an additional headache.

To maintain a steady flow, EACOP must be kept at a minimum temperature of 50°C. Tests showed that when the crude is flowing rapidly under high pressure, heating the pipe head to 80°C initially is sufficient to ensure continued flow, as cooling occurs gradually, keeping the temperature above the 50°C threshold for the full 1,443 kilometres.

But if the flow rate and pressure drop, the oil cools more as it travels, threatening to solidify and block the flow. To overcome this, two heating stations were added to the design to bring the crude back up to 80°C.

Heating cables will run the length of the pipeline using a technology known as Long Line Heat Tracing (LLHT), which uses resistance to generate heat when an electric current is passed through a specially selected high-resistance filament.

Because the temperature is so critical, EACOP’s conventional 24-inch wide carbon steel pipe had to be carefully redesigned. The fact that Uganda’s crude oil is sweet (with no corrosive impurities such as sulphur) means that the pipeline does not need to be lined on the inside, as such high quality crude oil has a minimal corrosive effect on steel. Therefore, the pipe only needs to be lined on the outside for protection.

In addition to the standard 400-600 micron thick fusion-bonded epoxy protective coating on the outside, engineers added a much thicker 70mm ‘smart’ layer of polyurethane insulation with special channels for the electrical heating elements, LLHT cables, and fibre optic cables needed for SCADA.

The whole pipe will be covered with a hard protective outer layer of 5-7mm high-density polyethylene, meaning EACOP effectively has four layers: inner steel, epoxy, polyurethane, and polyethylene.

So sophisticated is this layering that a coating factory is currently being built in Tanzania to ensure that each 18m length of pipe, already manufactured in China, receives the correct high quality treatment before it is sent out to be laid in the ground.

Because safety is EACOP’s top priority, the risk of internal leakage over the 25-year life of the pipe is reduced to virtually zero by using high quality steel and ensuring that the welds between each 18m length are tested at the time of installation and rejected if any defects are found.

Nevertheless, just to be on the safe side, the SCADA system detects small changes in pressure that could indicate a leak.

Block valves are installed every few kilometres along the pipeline so that if a leak is detected, the affected section can be immediately isolated, and only a short section of the pipeline is at risk of being drained.

Leaks in other African oil-producing countries have been caused by theft and sabotage, among other things. The plan to bury EACOP greatly reduces this risk, say the designers. In addition, SCADA can detect any surface disturbance along the right of way.

For most of the route, burial is possible because the pipeline runs through less rocky terrain, which was the intention. This means that a 30 metre wide metre wide corridor will be demarcated and kept clear of digging, quarrying, or other ground-disturbing activities.

Livestock will be able to graze as normal and gardens will be allowed in most sections to minimise disruption to rural communities.

Scouting for the EACOP route began in 2018, and after two years of consultations and surveys, it was decided that the pipeline would run 296 kilometres through southwestern Uganda from the collection and pumping station at Kabaale in Hoima District, before crossing into Tanzania, where it will travel 1,147 kilometres to the Indian Ocean coast at Chongoleani village near the port of Tanga.

A particular challenge arose off the coast of Tanzania: a steep slope in the terrain had the potential to create pressure surges caused by crude oil flowing downhill at high angles. To maintain pressure, two pressure reduction stations were incorporated into the design.

Ali Ssekatawa, PAU’s director of legal and corporate affairs, says those whose land is crossed were consulted, and compensation offered to legitimate claimants for loss of land, assets, and grazing rights.

In Uganda, 3,660 people were affected, while in Tanzania the number is 9,513 were affected. To date, 90 per cent of those affected in Uganda have accepted compensation packages, including 177 who opted for new homes away from the pipeline.

Negotiations are continuing, but if EACOP planners and local people cannot reach an agreement, both countries have legal systems that allow the government to compulsorily acquire land and compensate the affected parties through a transparent process.

The two production areas already sanctioned — Tilenga and Kingfisher — are expected to produce 230,000 barrels per day at peak capacity, requiring an export pipeline to maximise revenues from the country’s hydrocarbon assets.

To accommodate new production capacity from exploration areas yet to be developed, EACOP has been designed with a maximum flow rate of 246,000 barrels per day. This will allow the pipeline to be expanded in the future.

Uganda is also planning a refinery to meet local demand for petrol and other products. It is expected to consume up to 60,000 barrels per day, with the remainder exported through the pipeline.

The pipeline demonstrates Uganda’s commitment to developing its hydrocarbon resources in an open and responsible manner, Mr Abeinomugisha said. The country will benefit not only from the revenue generated by oil exports, but also from the transfer of engineering and technical skills through the project, he added.

Work is already underway on pumping stations, work camps, and storage facilities along the EACOP route, as well as the coating plant. The first 100 kilometres of pipe are expected to arrive by ship from China to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam in early 2024. After coating and welding, the first pipe sections are expected to be laid in the middle of next year.