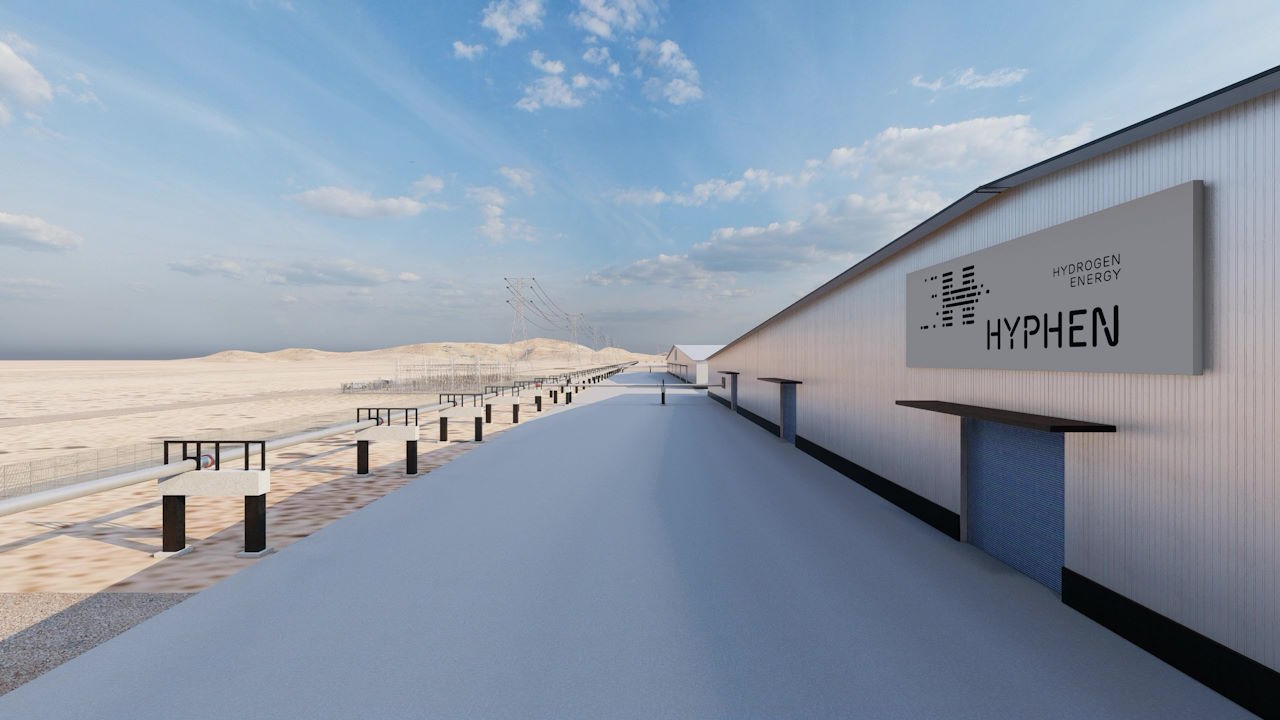

Efforts to build Africa’s nascent green hydrogen industry are underway, most notably in Namibia’s Tsau Khaeb National Park. In May, the Namibian government signed a feasibility and implementation agreement with Hyphen Hydrogen Energy for a green hydrogen production and supply project near the coastal town of Lüderitz. In June, the government agreed to take a 24 per cent equity stake in the $10bn project, which is almost equal to Namibia’s GDP.

Once fully operational, the project is expected to produce 350,000 tonnes of green hydrogen per year and create 3,000 permanent jobs (in addition to 15,000 temporary construction jobs). It could position Namibia as a major producer of low-cost green hydrogen. However, important questions remain about the project’s local value addition and how to avoid creating another extractive industry.

For decades, African countries have invested billions of dollars in fossil fuel energy systems, yet 600 million people on the continent remain without access to electricity. Even as global warming destroys ecosystems, undermines food security and exacerbates water scarcity, Africa remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels, with renewables accounting for only about 21 per cent of electricity generation. But the rapidly escalating climate crisis means there is an urgent need to shift the continent’s energy system away from oil and gas.

Rapid deployment of renewable energy could be transformative, helping Africa meet the twin challenges of climate change and underdevelopment. But to ensure access to electricity for all, such systems must be environmentally sound and socially inclusive. Ironically, the continent’s limited energy infrastructure means that African countries can leapfrog fossil fuels (avoiding stranded assets as the world transitions to renewables) and build a green economy based on renewables and designed to meet their needs.

Low-cost green hydrogen can expand energy access on the continent and accelerate the transition to renewables. And by creating local value chains, green jobs, and technology and knowledge transfer, it could contribute enormously to the development of producer countries.

But to reap these benefits, the development of green hydrogen in Africa must first and foremost serve African interests. This means that the processes and policies for producing and using green hydrogen must meet the standards set out in the Sustainable Development Goals, the ambitious global targets launched by the United Nations in 2015. They must also meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement and the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

They must also preserve the integrity of ecosystems, promote decent work and economic prosperity, foster social inclusion and cohesion, and respect human rights. Crucially, these goals can only be achieved through broad public acceptance: the free, prior and informed consent and participation of potentially affected communities.

Good governance and transparency in green hydrogen development could change the power relations between the developed world and African countries. Instead of falling into the trap of ‘green colonialism,’ these countries could build equal partnerships that address head-on issues of equity and ownership, inclusion, resource competition and displacement.

To be sure, there are significant risks associated with green hydrogen projects. Foremost among these are land-use conflicts, forced resettlement, expropriation, and other potential human rights violations. There are also environmental concerns, including the fact that production requires large amounts of fresh water. With one in three Africans facing water scarcity, the development of this energy source could exacerbate the problem and even cause or exacerbate conflict, particularly in Africa’s driest regions.

In addition, large-scale plants and export infrastructure could damage fragile ecosystems, destroy protected areas and endanger marine life. This is particularly true if desalinated seawater is used to produce hydrogen and the resulting brine is discharged untreated into local waters.

The biggest concern, however, is that green hydrogen produced in Africa could be exported elsewhere. This would defeat the purpose of developing renewable energy capacity on the continent. Instead of expanding access to electricity and building climate resilience, this new industry would be the latest in a long line of energy injustices. It would also be wasteful: converting hydrogen into derivatives such as ammonia — more suitable for transport — can result in 13-25 per cent energy loss, while transport itself requires high energy inputs.

Green hydrogen can drive economic growth and prosperity for producing countries. But to realise the potential of a hydrogen economy, African leaders must ensure that the industry is structured to achieve an equitable energy transition on the continent and to serve the needs of local communities, not foreign interests.

Amos Wemanya is a senior advisor on renewable energy and just transitions at Power Shift Africa.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023.

www.project-syndicate.org